Exploring Through Art

Living in Allentown when the College is in session and in Hamburg, Germany, when it is not gives Assistant Professor of Sculpture Frederick Wright Jones a broader perspective on his work and his teaching.By: Meghan Kita Wednesday, November 4, 2020 10:04 AM

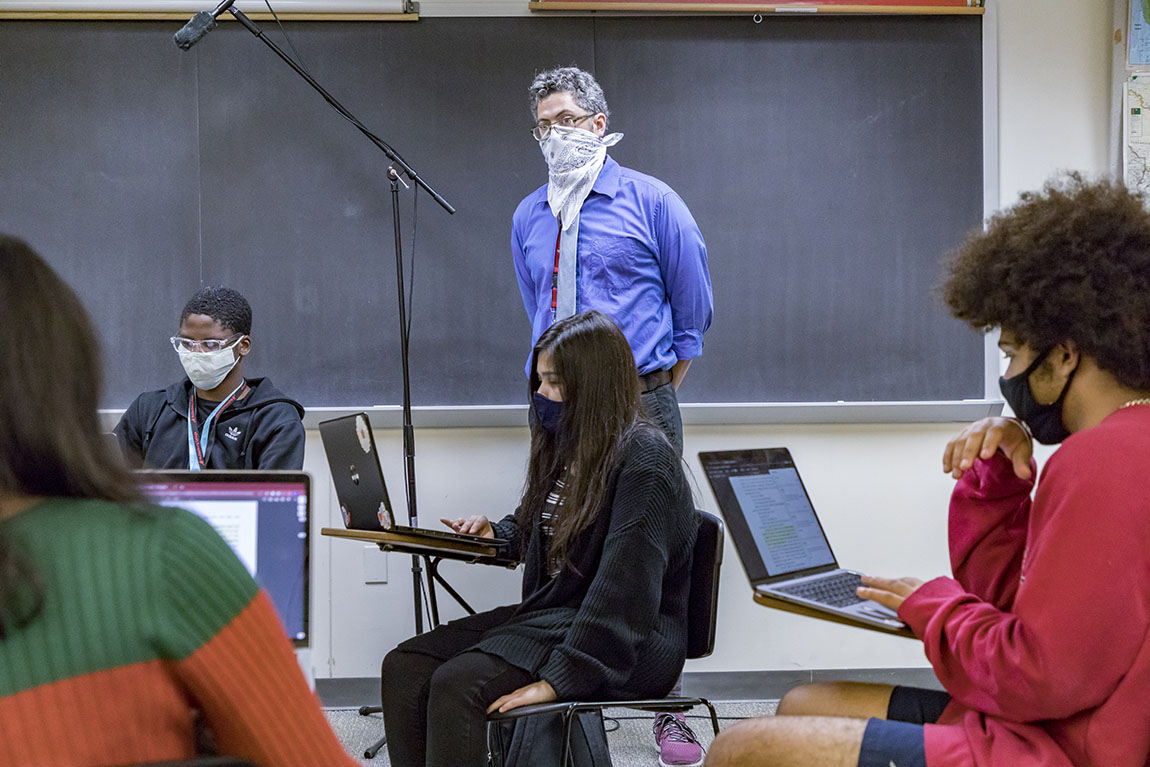

Assistant Professor of Sculpture Frederick Wright Jones in the sculpture studio. Photos by Paul Pearson

Assistant Professor of Sculpture Frederick Wright Jones in the sculpture studio. Photos by Paul PearsonThe viewer of the art installation “Confusion of Terms” enters a renovated barn and first sees what artist Frederick Wright Jones describes as “a small tar figure with a huge white grin, hair of toothbrushes and an American flag dress.” To the left, a wall of unfinished wood divides the room in half. Three vertical slits cut into the wall allow viewers to see what’s on the other side—rudimentary wooden workout equipment and a looped video of Jones using it while dressed head to toe in red, white and blue.

Jones, an assistant professor of sculpture at Muhlenberg, drew inspiration from former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick and “the political troubles he had gone through by speaking instead of ‘simply playing his game.’” The ideas driving “Confusion of Terms,” which was on display near campus in the fall of 2018, included incarceration, violence and national identity.

“A lot of the themes I’ve been thinking about are coming to a head right now,” Jones says, referring to the Black Lives Matter demonstrations following the death of George Floyd. “The frustration—of course there has been progress, but it’s always one step forwards, one step backwards.”

Jones splits his time between Allentown, about an hour north of where he grew up, and Hamburg, Germany, where his wife is from. When he’s abroad, his work often explores what it means to be an international citizen. In the United States, he focuses more on themes of history, politics and belonging, including “finding myself in America, coming to terms with that identity, with being African American,” he says.

Raised in a creative environment—his mother was an artist—Jones primarily drew throughout his childhood in rural Pennsylvania. As an undergrad at the Rhode Island School of Design, he took a woodcarving class, and that became his primary medium. His work includes objects that are completed and exhibited as well as idea-based projects, which include multiple elements and could be revisited at any time.

For example, he recently resurrected a project he started in 2008 as a master’s student at the University of Buffalo: the NRAACP, or the National Rifle Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Two events in the news at that time—the “Obama gun run,” in which firearm sales spiked after Barack Obama’s election, and the fatal police shooting of Oscar Grant III, an unarmed Black man—shaped Jones’ thinking about the project when it began. He carved puppets of American political figures, including Obama, Thomas Jefferson and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and exhibited a “meeting” of the puppets at a gallery in Buffalo, New York. He created T-shirts, hats and bumper stickers with phrases like “guns don’t vote for racists, racists do.” He launched a blog and a website.

When Jones moved to Hamburg in 2011, the project went dormant. He started at Muhlenberg in 2016, living in Allentown during the semesters and returning to Germany for winter and summer breaks. This spring, amid pandemic and protest, he relaunched NRAACP.org.

“There are a lot of things going on, and it's an election year,” he says. “It’s sad to watch but still hopeful with all the momentum. Publicity does change something, and people are starting to think differently. I don’t think art can save the world, but it’s a way of participating in the dialogue.”

Jones received a Faculty Rising Scholar Award in May, which offers select tenure-track professors who’ve completed their third-year reviews a course release and funds to hire a student assistant. He’d planned to have a student help him prepare for a January 2021 exhibition in Buffalo, but the pandemic has left the exhibition in limbo, and he does not have a student assistant. Still, he’s using the course release to complete a new piece, which he describes as “a large gear machine that lifts a hammer up that in the end will destroy the user.”

He’s teaching a first-year seminar (pictured above) as well as Sculpture I, the latter of which is being conducted entirely online. When courses transitioned online in the spring, he was focused on sculptural production—he would give students an idea and they would execute it. This fall, his assignments are more about how students might draw inspiration from their experiences or surroundings, how they might go from nothing to an idea to a work in progress to a finished product.

“When I consider a liberal arts education, all students, no matter what their discipline, they’re going to get the idea that you need to work and you need to produce. That’s something I don’t think I need to stress,” Jones says. “I was thinking, ‘What is the reason for an arts requirement?’ It’s about ways of thinking and problem solving. Art and making should be a process and an exploration.”