Why I Study Organometallic Chemistry

Professor of Chemistry Joseph Keane explains how he came to do his research and how it sets students up for postgraduate opportunities.By: Joseph Keane, as told to Meghan Kita Tuesday, December 5, 2023 04:44 PM

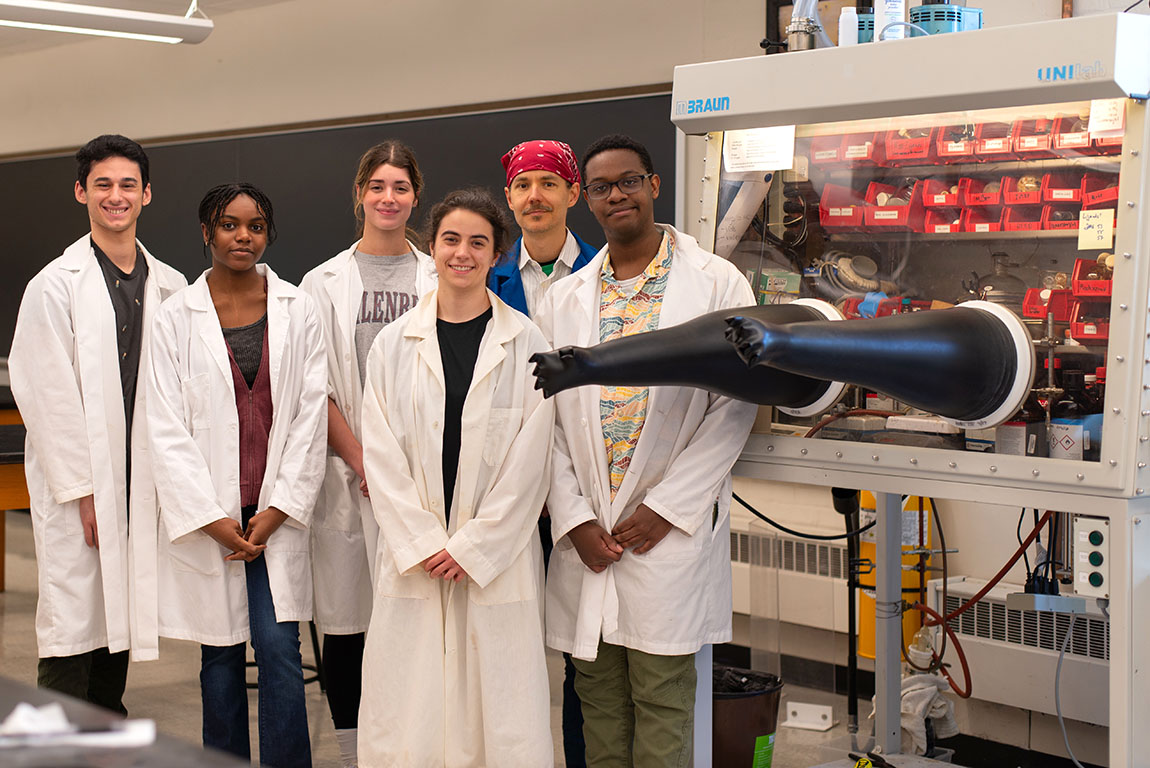

Professor of Chemistry Joseph Keane (second from right) with students in his lab in the summer of 2023. Photos by Lizard Foley ’24

Professor of Chemistry Joseph Keane (second from right) with students in his lab in the summer of 2023. Photos by Lizard Foley ’24This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of Muhlenberg Magazine. See the complete digital edition here.

My dad taught astronomy, physics and calculus at a small college, so I’ve always had a good sense of both science and college teaching. I wasn’t set on science, but my older sister, who was a biology and philosophy major, was home on a break and said, “I wish I studied more chemistry. You should major in chemistry.” I basically did what she told me to do for most of my life (and often still do), so I ended up studying chemistry at Lycoming College.

My first research projects were in synthetic chemistry (making molecules). After my junior year, I had the opportunity to do summer research at the University of Virginia. I had taken very little biology, so I was looking for a lab that was synthetic but non-biological. I found Dean Harman, who was doing strange, unnatural chemistry with osmium, reactions like nobody had seen before. I had a great experience there and went back to his lab for graduate school.

“I’m not going to change the world with the chemistry I’m doing. I do this research mainly to provide opportunities for the students.”

This field of chemistry, organometallic chemistry, deals with interactions between metals and carbon. In nature, they’re pretty rare — there are some enzymes and vitamins that have these kinds of bonds, and they’re weird. When it happens, you get some exciting, bizarre chemistry.

The example people are most familiar with is what happens in the catalytic converter of your car: The exhaust stream has nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides and unburned hydrocarbons that made it through the engine, and that gas passes over particles of interesting heavy metals like palladium, platinum or rhodium. When the organic molecules are sitting on the metal, the interaction breaks down the molecules so we don’t get as much pollution.

In my lab, I have students combine organic compounds with different metals using standard synthetic techniques like crystallization, distillation and so on. We work in glove boxes, which have big rubber gloves built into an enclosed space, because a lot of the compounds are air-sensitive. But I’m not going to change the world with the chemistry I’m doing. I do this research mainly to provide opportunities for the students.

After one summer working with me, students are very competitive for the National Science Foundation’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates programs, which let the students see if they like graduate research. At a university, they meet Ph.D. students who really are working 60, 70 or more hours a week for four or five years. That’s what we can’t give them here, that intensity of research. But unlike the undergraduate students at a big university, all of my students get their hands inside a glove box.