Computer Science Professor Fosters Connectivity

Associate Professor of Computer Science Jorge Silveyra supports students, both majors and non-majors, as they discover the potential applications of his field.By: Meghan Kita Tuesday, January 16, 2024 01:05 PM

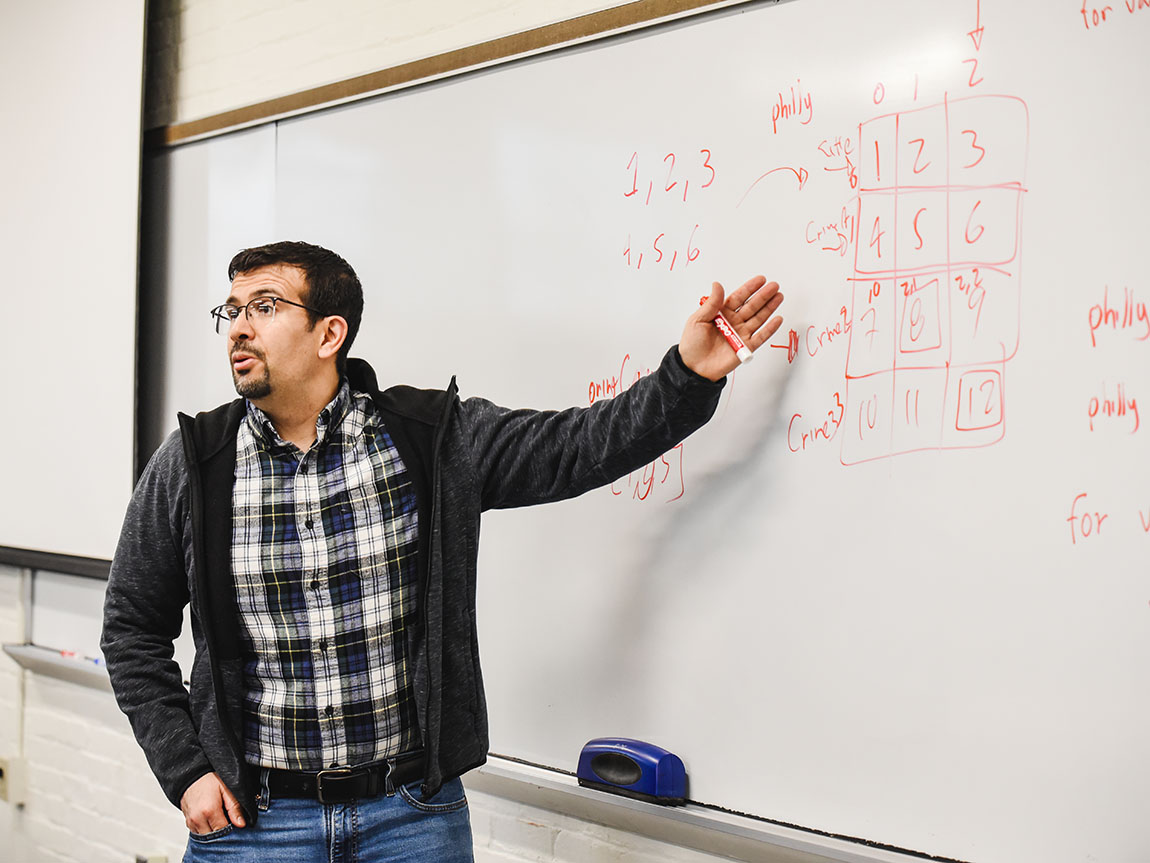

Associate Professor of Computer Science Jorge Silveyra teaches Intro to Data Analytics last spring. Photos by Kristi Morris

Associate Professor of Computer Science Jorge Silveyra teaches Intro to Data Analytics last spring. Photos by Kristi MorrisRight next to Associate Professor of Computer Science Jorge Silveyra’s office is a lounge filled with armchairs and tables, with large windows looking into the space from the suite of faculty offices. Affixed to one of those windows is a sign that reads “DO NOT TAP ON GLASS. YOU WILL FRIGHTEN THE PROGRAMMERS.”

It’s evidence that the computer science students who hang out there don’t take themselves too seriously. More evidence: the existence of “Nerd Club,” what students on the College’s Competitive Programming Team call themselves. The club meets weekly through much of the semester and up to four times a week when a competition is drawing near. Silveyra, the team’s coach, attends all the meetings and travels with the team to its competition each semester. It’s an integral part of the Muhlenberg experience for the budding computer scientists who participate.

“We have amazing alumni that have been part of Nerd Club, because it does help you with the type of interviews that really demanding jobs require.”

“Nerd Club is one of my favorite things I do at Muhlenberg,” says Silveyra, who came to the College in 2016. “I personally have become way better at programming just because I attend these meetings … Every time, by the time we leave, we’ve learned something.”

The team is also talented, taking first place at last spring’s Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges, Northeastern Region programming contest. It was the second consecutive win, and the third since 2019, for a Muhlenberg team. Silveyra sees the students bond, build skills and go on to impressive careers.

“We have amazing alumni that have been part of Nerd Club, because it does help you with the type of interviews that really demanding jobs require,” he says, noting that former team members have gone onto careers at Amazon, Warner Brothers Discovery and the Broad Institute, which is co-managed by MIT and Harvard.

While Silveyra develops close ties to these self-professed “nerds,” he is equally passionate about bringing computer science to both majors and to non-majors. His favorite course to teach majors is Data Structures & Algorithms, which comes after the two intro-level courses. He likens the intro courses to showing the students all the different types and shapes of Lego; Data Structures is when students begin to put the pieces together to create something useful. For the final project, students build a mini search engine, which Silveyra says is typically a graduate-level assignment. It becomes resume fodder for those undergrads who’ve completed the course, he says.

When it comes to non-majors, he believes in computer science education for all: “I could go into an endless number of examples of students that I had who were [business majors], they took a CS class and now that’s what they do in their job because they were the most CS savvy person in their cohort,” he says. “Having computer literacy can be a game-changer.”

“The fact that they have a liberal arts education helps them to be better speakers and writers. Our job is to give them the tools to problem solve, to think, to be ethical. It’s not just the computer science classes on their own [that lead to success]. It’s the whole package.”

Data Analytics is a course that commonly attracts non-majors, and he assures the students that by the end of the semester, they’ll be able to do something useful. The course gives students a better understanding of how software is made and what it’s capable of doing — critical for those who aspire to manage large teams that could include people who write software — and skills that transcend any given program.

“I try not to teach technologies,” Silveyra says. “Technologies get outdated very quickly. I try to teach concepts.”

Silveyra’s personal educational background spans disciplines: As an undergrad, he was trained as a computer engineer (working with both hardware and software) in his home country of Mexico. He pursued computer science (primarily software) as a graduate student in Texas, where he worked in the lab of a computational epidemiologist. He had to take classes in immunology, biology, biostatistics and genetics to understand the research, which involved coming up with models to replicate human immune-system responses.

He recently drew on his public health background when he co-taught the Public Health in Panama Muhlenberg Integrative Learning Abroad (MILA) course, which culminated with two weeks in Panama with the students and co-teacher Associate Professor of Spanish Erika M. Sutherland. Silveyra’s interests outside of academia include cycling, playing video games (Zelda is his favorite) and going to the gym — he’s there almost every night, getting to know students and colleagues.

What drew Silveyra to a small liberal arts institution, an educational model that has not historically existed in Mexico, was not necessarily the breadth of curriculum but the close relationships he’d be able to form with students. The students he met when he visited Muhlenberg on his interview, he recalls, were engaged at a level he hadn’t seen at the larger institutions he’d attended. The close relationships have certainly materialized at Muhlenberg, but he’s also seen the power of the liberal arts as his students have gone out into the world.

“The fact that they have a liberal arts education helps them to be better speakers and writers. Our job is to give them the tools to problem solve, to think, to be ethical,” he says. “It’s not just the computer science classes on their own [that lead to success]. It’s the whole package.”