A Parallel Universe

Through his work on VR software, Evan Sforza ’07 helps create a welcoming place for people from around the world to meet.

This article originally ran in the Spring 2020 issue of Muhlenberg Magazine, and the introductory paragraph references the print publication.

By Meghan Kita

This is the beginning of a story about Evan Sforza ’07, a designer at Microsoft who works on virtual reality software called Altspace. You probably read the headline on page 32, and then you flipped over page 33 to find this first paragraph. You know to turn the right-hand-side page to see what’s next because you’ve been reading magazines and books for years. You expect to look at the bottom of this page and see it numbered; you expect to see photos with captions sprinkled throughout the article. There is an established way that humans interact with print media, and this magazine is designed with those conventions in mind. But what happens when a technology is so novel that it has no conventions?

“Design in VR is still such a very new thing,” Sforza says. “It’s a lot about empathy, trying to understand the other human being that’s picking up the device and interfacing with the software you design. It’s about making sure people from all walks of life have the potential to understand what you’re trying to do.”

What Altspace is trying to do is to bring early adopters of VR technology into a world where they can interact in a more immersive way than they could via text message, phone or video chat. The term used in the VR industry to describe this is “presence,” which means “actually feeling like you’re there and feeling like someone is with you,” Sforza says. His job involves figuring out why someone would want to be there, how they might interact with others and what things there are to do in this new environment. A positive user experience plays a critical role in the Altspace team’s overarching goal: to create a space that’s worth coming back to again and again.

What Is VR?

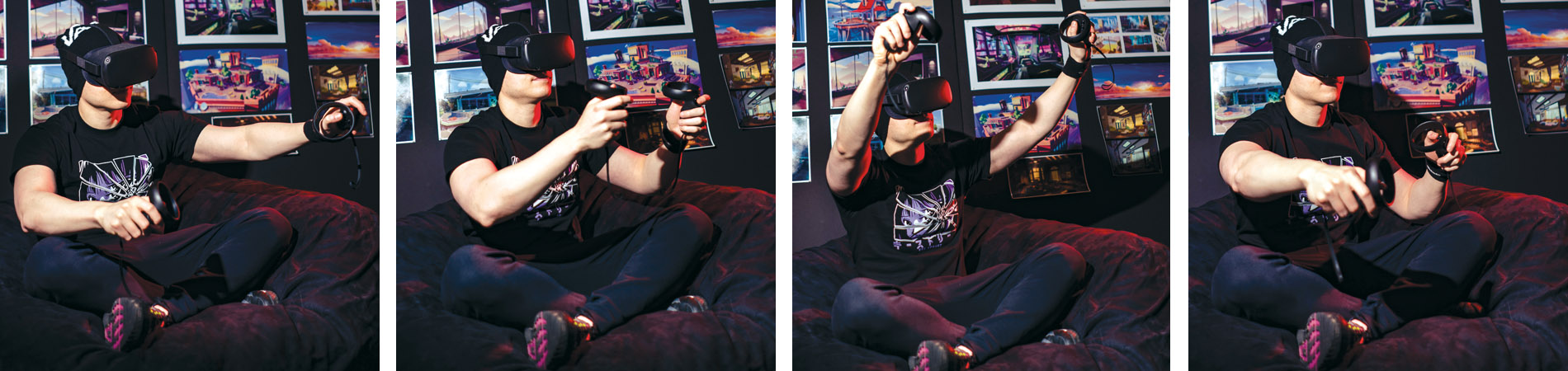

Most people reading this won’t have experienced VR personally—while upwards of 170 million VR headsets have been sold, they’re far from commonplace. The main piece of hardware, the headset, provides audiovisual immersion. Most headsets connect to an external computing device (a gaming system, desktop computer or phone), though options with built-in processors (called “standalone” headsets) are starting to come to market. The headsets have two lenses inside, each with their own display. Each display renders a slightly different image, which are offset from one another by the distance from one eye to the other. Audio can be built-in or delivered through connected headphones. Controllers for each hand allow those movements to be reflected in the virtual world. The best-selling hardware brand in Q4 of 2019 was the PlayStationVR, followed by the standalone Oculus Quest. Altspace is software that’s compatible with most VR headsets.

Sforza, who began working at Altspace in 2016, describes it as “the next evolution of chat rooms,” a place where strangers can interact. It’s not unlike a bar or a club, he says: “This is just a means of doing what humans have been doing for millennia, from the comfort of our own homes, without all the additional effort and baggage that comes with face-to-face interaction.” Users are able to move through different worlds (with names like Mythical Library, Brooklyn Rooftop Hangout and Space Museum) and speak to one another using the microphones on their headsets.

Putting a bunch of strangers in an environment together comes with both potential delights and definite challenges, one of which is the relatively small number of people who have the technology: Any given user’s real-life friends likely don’t have VR headsets of their own, Sforza says. So how can Altspace ensure its 30,000 monthly active users—a tiny number compared to conventional social media platforms but a large one in the new frontier of VR social applications—are having enough fun to be active next month, and the month after that?

Altspace’s leadership team is focusing most of its energy on encouraging events— concerts, comedy shows, book launches, even small get-togethers. Sforza has been working to make it easy for users to create an event and invite other people. He and his team are also exploring other ways to bring together users with similar interests.

But Sforza’s true passion lies in the little details that make the virtual environment feel more like the real world, that give it “presence.” For example, he’s working on a new line of avatars with additional features like eye movement, even though none of the hardware currently is able to track eye movement. The idea is to program in the ways humans’ eyes might move in certain situations, like making brief eye contact when you cross paths with someone else.

“We’re thinking through, What are the important features of the human body and human socialization that we could turn into computer code or an interface?” Sforza says. “We want to create an experience that’s as immersive as possible. We want you to feel like you’re talking to another human being.”

The “Why” of Design

Sforza’s passion for tech—more specifically, for video games—is how he ended up as a philosophy major at Muhlenberg. Early in his time at the College, he was perusing job descriptions at Bungie, Inc., the studio that created the popular Halo series. He noticed that their game designer listings said they’d appreciate candidates with a philosophy background.

“I really enjoyed going into an environment in Halo and trying to think like a designer,” he says. “I began to look at the construction of the virtual world as being very intentional. I wanted to understand game design and the reason and philosophy behind the design.”

He always liked drawing, so he added an art minor to figure out where the skills he had could fit into a game development studio. Then, he was inspired to take English courses, enough for a second minor, to explore the reasoning behind narratives and the subtext beneath them. By graduation, he had his sights set on a career as a concept artist, the person who imagines what elements of a game might look like. He had some internships and decided it wasn’t for him: “I actually cared more about the ‘why’ than how something looked.”

He asked a boss where he should go to grad school to make the jump to game design, which is how he ended up at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts’ Interactive Media & Games Division. “I originally went there wanting to make first-person shooters and other video games,” he says. “But, after interacting with the professors and seeing the power of software, how much it could influence human behavior and society at large, I got really interested in social media and social networks.”

But if there was one opportunity that could pull Sforza back toward games, it was an opening with Halo. Shortly after grad school, he landed a job at 343 Industries, the company that acquired Halo in 2012. There, he was a multiplayer designer, working on the most social element of the game. He helped design a new game mode for Halo 5 called Warzone that combined team play with opportunities to defeat AI characters for points.

“For me, there was a certain magic, mystery and allure surrounding Halo, but, when I went to work on it, I discovered that it wasn’t exactly fulfilling my desire to connect people through cyberspace,” he says. “I knew VR was going to be important. I needed to work on it.”

So, he began searching for a new role in that field, one that preferably had a social application, and Altspace fit the bill. He went from working on a team of more than 600 to a team that’s currently about 30 people. “The amount of influence any one person gets is a little bigger,” he says.

The Future of VR

There are some immediate technical challenges with VR that Sforza encounters in his everyday work. For example, the current sensor placement makes it impossible to accurately track a person’s arm and leg movements, which is one reason Altspace avatars just have floating hands. Ideally, more of the human body would be represented in VR, which would likely require hardware with more sensors as well as eye-tracking. Long-term, Sforza envisions the ability for users to create avatars that actually look like them by undergoing high-resolution scans of their bodies.

In order for VR to become more widely adopted, Sforza says, the hardware needs to evolve. Right now, there are only a small handful of standalone headsets available, and they still cause the user to lose awareness of their surroundings. The future might lie in mixed-use devices that don’t yet exist: Currently, there are augmented reality (AR) devices, like Microsoft’s HoloLens, which overlay some digital content onto what you’re seeing in real life, and VR devices, which are completely immersive.

“When you have this visor over your face, if we color every pixel, you’re in VR. If you see the real world behind it, it’s AR,” Sforza says. “With the right device, you could go from VR to AR and back again.”

Such a device would need to be able to color a user’s peripheral vision, but in order for it to be widely adopted, it would probably have to look more like a pair of glasses than a pair of ski goggles. “I don’t know how readily people are going to put on a headset with a big glass visor and go to work at Starbucks or any regular place,” Sforza says.

Right now, some employers are utilizing devices that are currently on the market. For example, the Air Force uses VR to provide some pilot simulation training. In the medical realm, VR and AR technology have been used to help surgeons visualize a problem before operating, to train new doctors and to treat mental health issues in patients. But these largely behind-the-scenes applications won’t necessarily help normalize the technology as part of everyday life. In other words, both VR and AR devices have a long way to go before either becomes the next smartphone.

“With your phone, it’s in your pocket. It’s always on your person. To use it, you reach in, pull it out, hit a button,” Sforza says. “When using a VR or AR device is as quick or as simple, that’s when it’ll probably start to become more ubiquitous.”